Primary Source Materials are first hand accounts of events, like this:

Primary Source Materials are first hand accounts of events, like this:

“I was too young to remember her. I do not have the faintest recollection of her. I was told my Aunt Hannah made a white dress for me with lace beading and ran a black ribbon through this beading for the burial services.

“The day of the services Aunt Hannah was holding me in her arms and when they closed my mother’s casket I waved my hand and said, “bye-bye, Mama.”

The day I copied those words, I stopped and put my head down on the keyboard. I wept for both Carrie who died following her second childbirth and also for my grandmother who lived 91 more years missing her beautiful, kind and loving mother.

Primary source materials is not a glamorous term and sounds staid and boring, but it can make scenes come alive and inspire curiosity:

“Spill it! We’re aching to know where and how you spent the night? Why the Winchester? And for whom the book on etiquette?” (Rev. R. M Dickey; Gold Fever)

Newspapers and diaries are excellent sources of information–primary, the first places things were reported.

Historians insist history cannot be understood without them–the eyewitness accounts of people on the ground.

Often, their poignancy speaks much louder than anything an author can imagine. As he prepared to fix his bayonet for the battle of Cold Harbor during the Civil War, one soldier scribbled the date on the last page of his diary followed by the fateful words:

“I died today.”

Adapting Primary Source Material

I like to use primary source materials while writing historical fiction because it makes the story feel more real. I start with basic information about the location and history, and then scour the

Internet and libraries to find actual information written by people during the time frame.

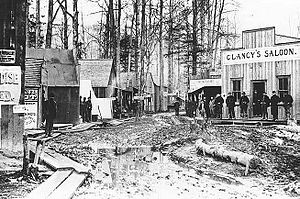

For my novella The Gold Rush Christmas, my best source was Rev. R. W Dickey who spent the 1897 winter in Skagway, Alaska and wrote about building the Union Church. He mentioned townspeople, described what he encountered, and quoted unusual events in his book Gold Fever: A Narrative of The Great Klondike Gold Rush, 1897-1899.

He was the primary source of the amazing tale of the Skagway “sporting women,” “soiled doves” and “unfortunates,” as polite society called prostitutes.

When church member Mollie Walsh asked him to visit one of these women, the as-yet-to-be-ordained Rev. Dickey hesitated. But he went, reminded the dying woman about Jesus and “how he came to search for us and bring us home to our loving heavenly Father.”

“The funeral service two days later was held in the church, which scandalized some people. The girls of her own class were in attendance–practically all of them–their painted faces and showy ornaments marking them out from the few women of the other class. Some of the latter sat aloof and looked their disapproval.”

You can picture them, can’t you?

“It was a strange scene–probably fifty girls on their knees as we carried the coffin down the aisle.”

Rev. Dickey needed to visit the hospital and didn’t go to the cemetery, “but I paused long enough to watch the men reverently carrying the body of their erring sister toward her last early resting place, confident that Jesus to Whom she had looked had brought the wandering lamb home.”

I didn’t have enough extra words in my tightly-written 20,000 novella to include all of Rev. Dickey’s details or lovely turns of phrase. I had to condense the story line and so many of his actions were transferred to Miles, a not-ordained seminarian whose sense of propriety ran into a number of “how can you not?” questions in “The Gold Rush Christmas.”

Rev. Dickey ran into Captain O’Brien of the steam ship Hercules, who was curious about local news. He told the story of the sporting woman’s death and the sobbing unfortunates in his church, mentioning his own sermon. The captain listened with interest and then had a question:

“Do you think any of them do it, leave off, I mean . . . Get word to them that on my return trip . . . I’ll take all who want to go to Vancouver or Seattle. It won’t cost them a cent.”

When the reverend pointed out they’d have no money and would have to return to their trade, a packer standing nearby butted in:

“I’ll give the Captain a check for whatever he thinks he may need. Would a thousand do?”

The town conman, Soapy Smith, wasn’t likely to let his primary source of income go without a fight. The good men of Union Church, however, led by Rev. Dickey prevailed on the fearful sheriff to help the women. As the sun set that night, a group of church people escorted 40 prostitutes to the Hercules and waved them south.

An amazing story.

I’ve read a lot about the Alaskan Gold Rush. I’ve been to Skagway, Alaska and seen the Mollie Walsh statue in the park. I’ve read countless tales of missionaries, but had never heard of this one before.

I had to go to the primary source material to find out.

Where do you read for information when you want to know history? Do you like to read memoirs and personal histories, or do you prefer the history books?

Tweetables

How 40 prostitutes escaped 1897 Skayway Alaska. Click to Tweet

Using Primary Source materials for a better story Click to Tweet

Stranger that fiction: 1897 Skagway prostitutes escape Click to Tweet

I try to balance my reading of memoir and history. Memoir preserves the emotion, but can be inaccurate when it comes to fact, and history rarely has the personal touch (with some exceptions, like Rick Atkinson’s ‘Liberation Trilogy’).

Something interesting about memoir…when it’s written close in time to the events of interest, it has the liveliness of action and atmosphere, but can be frustratingly lacking in meaning derived from introspection.

A case in point is Charles Lindbergh’s stories of his New York-to-Paris flight. Shortly after the 1927 event, he wrote “We”, which reads as a straight narrative.

Over twenty years later, in 1953, “The Spirit of St. Louis” was published. Lindbergh had lived through a lot in that time – the kidnapping and murder of his son, ostracism for his isolationist views in the years leading to WW2, and the work he undertook during the war (showing pilots how to get the most from their aircraft, and, as a civilian, shooting down at least one Japanese airplane).

“The Spirit of St. Louis” is much broader in scope, telling the story of Lindbergh’s early life in Minnesota, and weaving that past into the arc that inevitably led to his long, lonely flight. His thoughts become metaphysical, finding in the night over water a bridge between this world and the next, vouchsafing him with secrets that he could not quite remember when he rejoined the world, coming to earth from his solitary orbit.

The books serve different purposes, but to understand the effect of history on the heart of a man, it seems that a gestation period is needed.

I agree with you Andrew. I read a memoir this weekend by a thirty year old and while she told a compelling story, I don’t believe she had enough time to grow into either the maturity nor the wisdom her book required. I suspect, therefore, it is a spiritually dangerous book and I’m troubled.

The difference between We and The Spirit of St. Louis was Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Charles Lindbergh, a eugenisist, had the wisdom to marry a fine writer–who edited for him!

Wow–what an incredible story, Michelle! Now I want to read both your book and the memoir that inspired it. 🙂 Thanks for the reminder of the value of digging up primary sources!