We headed to the western front to see the land and explore the trenches.

We’d visited museum examples of World War I trenches in the Auckland (New Zealand) War Memorial Museum; at the Musée de l’Armé in Paris; at the Imperial War Museum in London and I’d stood in one in downtown Indianapolis’ World War Memorial just last month.

It’s the miserable trench warfare people think of when you mention World War I.

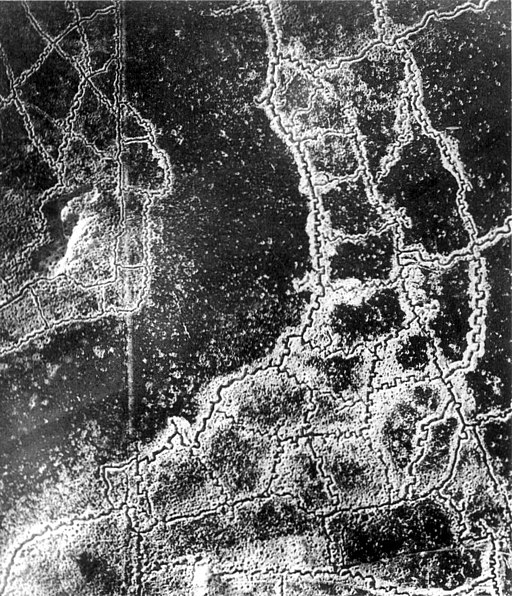

The Allies and the Axis powers built 500 miles of zigzagging trenches all the way from the English Channel to the foothills of Switzerland.

It represented stalemate as they stared at each other, often through periscopes, across a no-man’s land of barbed wire and land mines.

Absolutely miserable

Basic trenches

Basically dug eight or so feet into the ground, trenches provided a cover of-sorts in a war that didn’t have much in the way of airpower.

Planes in 1914-1918 were primarily used as reconnaissance–to know where things were–rather than as weapons. Airplanes may have had machine guns by the end of the war, but bombing capabilities were limited.

Instead, the men dug into the ground. When it began to rain, they put down “duck board” to walk on. They dug latrines into the walls of their trenches. Rats and other vermin, particularly lice, thrived in the conditions.

Many soldiers came down with “trench foot,” a disease resulting from spending so much time in wet socks and boots.

The smell was atrocious and, really, they were simply living in open holes to the sky.

Over the top

“Going over the top,” meant clambering out of the deep furrows carrying weapons and heavy packs into the nightmare of barbed wire and machine gunfire.

Horrific.

The Somme today

100 years of rain and silt filled in most of the trenches save for those specifically set aside for tourists.

We did not tour any intact trenches, instead, we wandered among the rumpled earth of the Somme. We saw the remaining lines of where men once burrowed into the ground in the hopes of staying alive another day.

At the South African memorial site, our guide could showed us trench remains.

As the rain pattered down, we hurried through the trees to curious indentations in the ground.

As the rain pattered down, we hurried through the trees to curious indentations in the ground.

They looked more like humps left behind by giant moles–which I suppose they were. The rainwater puddled in the water, just as it had 100 years ago.

I wore tennis shoes that day, which quickly became soaked.

Unlike the men who battled trench foot all those years ago, I knew I’d be in dry shoes and warm clothes by the end of the day.

My husband wore his brand new trench coat–a specific type of rain coat made of water-resistant gabardine.

Designed and created by the Burberry Company and so loved by the officers who wore it, it became a fashion statement after the war.

He was dry all day.

German trenches

Further down the road, our guide took us off into the woods to show us an area he had found while exploring.

“These were German trenches,” he explained, sketching with his hand where each side had lined up. “They’re surrounded with barbed wire now because it’s considered an archaeological site. Teams will come in and excavate. We can just look.”

If you squint you can see the rows of indentations that marked the trench lines.

If you squint you can see the rows of indentations that marked the trench lines.

Notice how the trees grow up from different levels of soil. The trees are all less than 99 years old, of course.

If you’d like to see and learn more about just what happened in the Somme trenches, see this video on Youtube.

The trenches were lengthy and connected to the back lines. Sometimes there would be as many as 12 different trenches to overrun once soldiers survived the dash across no man’s land.

Absolutely nightmarish.

Quality trenches

The Germans perfected trench building and by 1918 had shored up the earthen sides with cement and dug up to 40 feet underground.

They had hospitals, dry beds, and even a train system to move artillery to their front lines.

The British had dirt dug outs and never-ending rain.

Really, as I read G. J. Meyer’s A World Undone and other books about World War I, I’m amazed the Germans did not win the war. The quality of their trenches and pillboxes surely should have given them the edge in battle.

Meyer thinks the Americans entry in the war in 1918 made the difference.Our guide was not so sure.

Regardless, it was sobering to contemplate.

What do you know about World War I trenches?

Tweetables

WWI trenches are still there Click to Tweet

The misery of WWI trenches, even today Click to Tweet

What were WWI trenches like? Click to Tweet

‘Trench warfare’ has to be one of the nastiest phrases in history.

The trenches were really mandatory, because development of the science of artillery made aboveground movement suicidal in the long term. Trenches gave a modicum of protection, save from a direct hit.

One of the things most don’t realize is that when troops went over the top, they maintained a walking pace in their assault on enemy trench lines. They didn’t run – they didn’t ‘charge’.

Sounds crazy, but it was again dictated by artillery. A creeping barrage would be set, with shells hitting a fixed distance ahead of the advancing troops, and moving forward at their pace. Hence it did not pay to run! One would only overrun the barrage.

The artillery was basically designed to keep the enemy’s heads down, and prevent them from using machine guns on the horribly exposed advancing troops. (Enemy artillery emplacements would have been subject to a preassault barrage, as well – their locations pinpointed by aircraft and observation balloons.)

‘Trench clearing’ was done with combat shotguns (the use of which was later limited by the Geneva Convention) called ‘trench brooms’. The Thompson sub-machinegun of Chicago gangster fame was also developed for this purpose.

The most successful way to wage war against an enemy dug into a trench system was called ‘bite and hold’. It;s about what it sounds like – an advance to a predetermined line, followed by consolidation. The cost in casualties was necessarily high, and progress painfully slow, but the technology needed for quick breakthroughs and their exploitation (in the form of fast, mechanized units) didn’t exist.

The American entry into the war did doom the Germans, since America had essentially unlimited resources. and Germany’s resources were nearly exhausted. They did attempt to turn the Allied lines in the spring of 1918, attacking across the old Somme battlefields. The plan was to punch through the trench system, and ‘roll up’ the lines by turning behind them.

Needless to say, it didn’t work. The Germans were essentially finished by the fall of 1918. They could have prosecuted the war for a few more months, but the arrival of massive American forces in 1919 would have brought the war to a swift end.

There is another interesting aspect of trench warfare, and that is the ‘relationship’ that developed between the opponents. This was most clearly defined in the 1914 Christmas truce, which developed spontaneously (and against the wishes of the generals). British and German troops came out of their trenches and met in no-mans-land, to exchange food and cigarettes, and take a break from the war.

This didn’t occur again (at least on a significant scale) until the Armistice. At the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, a pilot over the lines later described the scene – hundreds of grey and khaki-clad figures suddenly poured out of their trenches, to meet halfway, hugging and dancing.

There is a lesson there. I hope one day we learn it.

Amen.

The history of WWI is maddening–from cousins who went to war reluctantly and then didn’t have the means to call back the troops once it they were mobilized, to generals who apparently didn’t have children the way they sent young men to the slaughter. It’s a sludging trudge through horror.

I think you’re off a year, Andrew, Germans finished by fall 1917; the Americans were over there by spring 1918 and then war ended that November. Treaties and so forth were signed in 1919. A small point.

My novel, I’m a third done, looks at the war out of the corner of the heroine’s eyes, but is focused on finding something positive amid the horrors around her. She’s about to leave London for Egypt. We’ll see how she (and I) do.

When through these histories, you can understand why Hemingway and Fitzgerald’s peers in Paris in the 1920’s were called “the lost generation.”

Thanks for adding your expertise.

What I know of I read in Sebastian Barry’s (hard to read but enormously moving) book “A Long, Long Way.”