How do you turn a true story into a fictional tale?

How do you turn a true story into a fictional tale?

Carefully.

The mythology of stories is there are, really, only seven basic plots an author can write.

A quick glance around suggests that can’t possibly be true. How can there be millions of books if there are only seven plots?

The creativity of the authors–which involves their ability to “recast” a plot into a different time and place (Shakespeare was a master at this, when he wasn’t just stealing the story from antiquity)–and the endless variations of those seven plot lines.

History can be an excellent place to find stories to retell and I did so when writing my novella “The Gold Rush Christmas” for A Pioneer Christmas Collection, newly rereleased in September 2015.

As good ‘ole Mrs. Klocki, my 8th grade history teacher used to say, “I don’t know why you bother with fiction. You should read nonfiction. Not only is it even more hair-raising than fiction, but it’s also true.”

That’s probably why I enjoy reading and writing historical fiction.

Adapting Primary Source Material

I like to use primary source materials while writing historical fiction because it makes the story feel more real.

I start with basic information about the location and history, and then scour the Internet and libraries to find actual information written by people during the time frame.

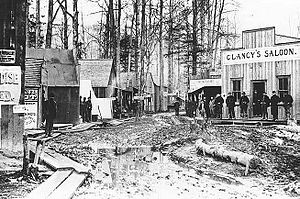

For my novella “The Gold Rush Christmas,” my best source was Rev. R. W Dickey who spent the 1897 winter in Skagway, Alaska and wrote about building the Union Church.

He mentioned townspeople, described what he encountered, and quoted unusual events in his book Gold Fever: A Narrative of The Great Klondike Gold Rush, 1897-1899.

He was the primary source of the amazing tale of the Skagway “sporting women,” “soiled doves” and “unfortunates,” as polite society called prostitutes.

Dealing with the prostitutes

When church member Mollie Walsh asked him to visit one of these women, the as-yet-to-be-ordained Rev. Dickey hesitated.

But he went, reminded the dying woman about Jesus and “how he came to search for us and bring us home to our loving heavenly Father.”

“The funeral service two days later was held in the church, which scandalized some people. The girls of her own class were in attendance–practically all of them–their painted faces and showy ornaments marking them out from the few women of the other class. Some of the latter sat aloof and looked their disapproval.”

You can picture them, can’t you?

“It was a strange scene–probably fifty girls on their knees as we carried the coffin down the aisle.”

Rev. Dickey needed to visit the hospital and didn’t go to the cemetery,

“but I paused long enough to watch the men reverently carrying the body of their erring sister toward her last early resting place, confident that Jesus to Whom she had looked had brought the wandering lamb home.”

I didn’t have enough extra words in my tightly written 20,000 novella to include all of Rev. Dickey’s details or lovely turns of phrase, even though he appears in a cameo role.

I had to condense the story line and so many of his actions were transferred to Miles, a not-ordained seminarian whose sense of propriety ran into a number of “how can you not?” questions in “The Gold Rush Christmas.”

The steam ship captain

On his way to the hospital, Rev. Dickey met Captain O’Brien of the steam ship Hercules, who was curious about local news.

He told the story of the sporting woman’s death and the sobbing unfortunates in his church, mentioning his sermon. The captain listened with interest and then had a question:

“Do you think any of them want to leave off? I mean . . . Get word to them that on my return trip . . . I’ll take all who want to go to Vancouver or Seattle. It won’t cost them a cent.”

When the reverend pointed out they’d have no money and would have to return to their trade, a packer standing nearby butted in:

“I’ll give the Captain a check for whatever he thinks he may need. Would a thousand do?”

Soapy Smith’s reaction

The town con-man, Soapy Smith, wasn’t likely to let his primary source of income go without a fight. The good men of Union Church, however, led by Rev. Dickey prevailed on the fearful sheriff to help the women. As the sun set that night, a group of church people escorted 40 prostitutes to the Hercules and waved them south.

An amazing story.

I’ve read a lot about the Alaskan Gold Rush.

On a visit to Skagway, Alaska I saw Mollie Walsh’s statue in the park. I’ve read countless tales of missionaries, but had never heard this one before.

I enjoyed the true stories–and the photos–in this book!

I had to go to the primary source material to find out.

Where do you read for information when you want to know history? Do you like to read memoirs and personal histories, or do you prefer the history books?

Tweetables

How 40 prostitutes escaped 1897 Skagway Alaska. Click to Tweet

Using Primary Source materials for a better story Click to Tweet

Stranger that fiction: 1897 Skagway prostitutes escape Click to Tweet

Thoughts? Reactions? Lurker?